Less than 1g to kill, and 1 minute to purchase: A deep dive into toxic ‘street pesticide’ terbufos

Orrin Singh, Katlego Jiyane, Nica Richards and Abigail Javier

13 November 2024 | 5:10After purchasing terbufos from a street vendor and sending it off for testing, EWN delved into the deadly nature of terbufos, and the pain it has caused its innocent victims.

It’s midday in Kanana, Tembisa. The sweat lined the brow of a street vendor dressed in blue overalls who seamlessly navigates the busy street of Strandloper.

Mops, brooms, feather dusters, cell phone charging cables, lights, and a range of home cleaning items innocently hang over his shoulder.

But concealed in his black backpack lies a deadly poison manufactured to kill.

Known commonly as “halephirimi” among locals and used for killing rodents, it took just over a minute for EWN to purchase the substance from the street vendor – costing just R10.

His only advice?

“Just put it underneath your bed. You’ll find the rat dead under the bed.”

No warning labels, no instructions of how to properly handle it – he hands us death disguised in small black granules wrapped tightly in a translucent packet.

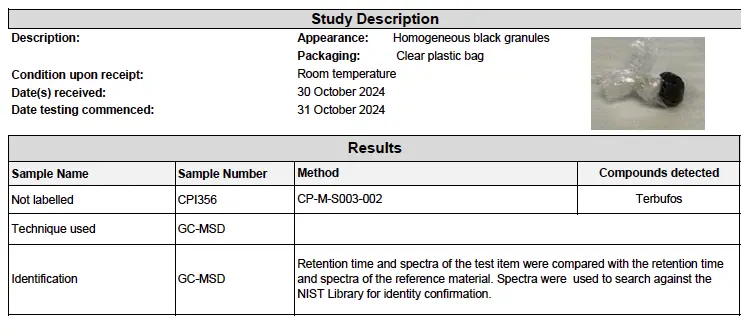

EWN sent the substance for analysis at a private laboratory in Pretoria. The results positively identified the chemical as terbufos – the active ingredient of a highly toxic organophosphate used to kill pests, for legal use only in the agricultural sector, predominantly for the growing of potatoes and maize.

The results show that the black granular substance we sent for testing is positive for terbufos. Picture: Supplied

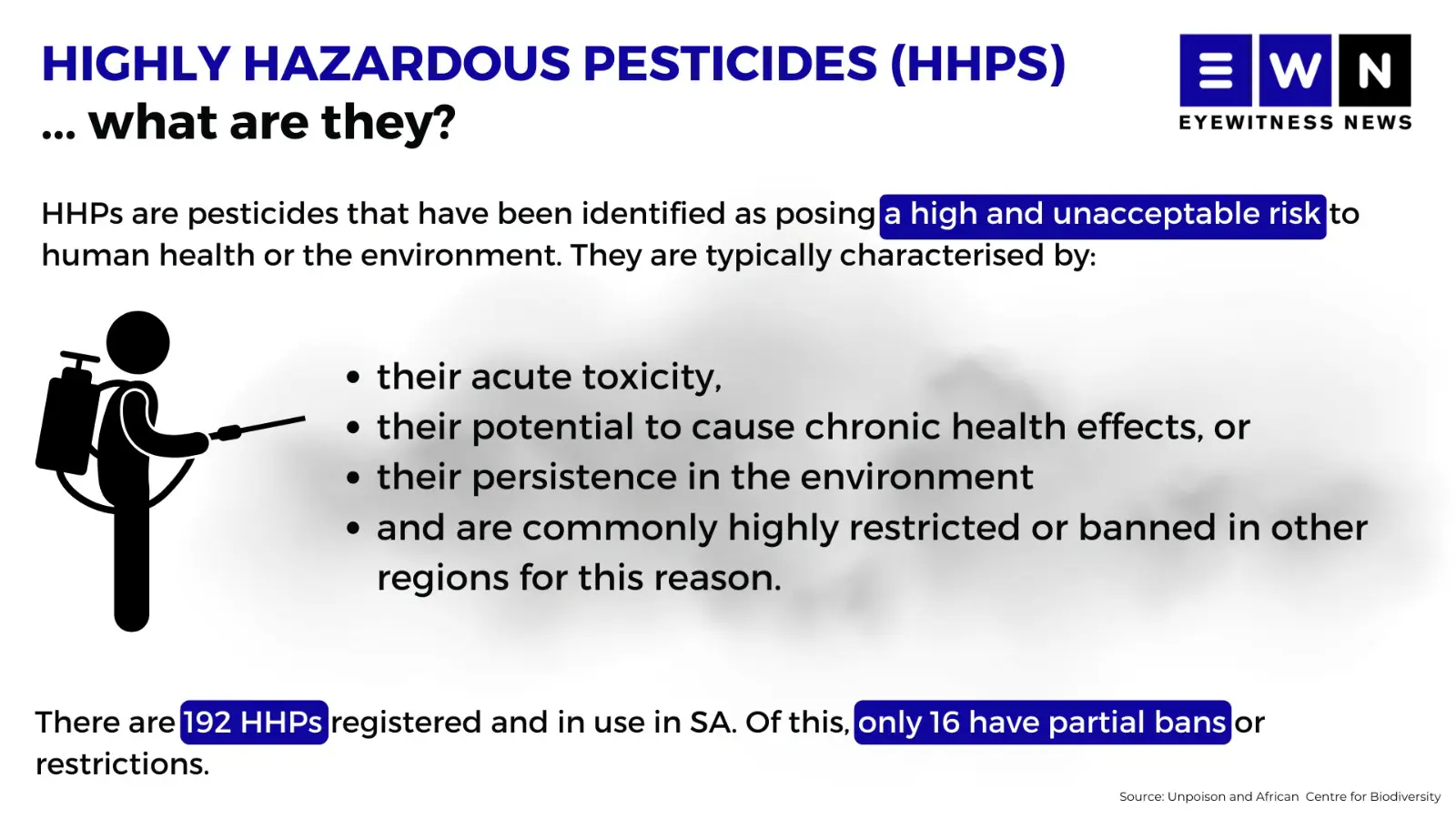

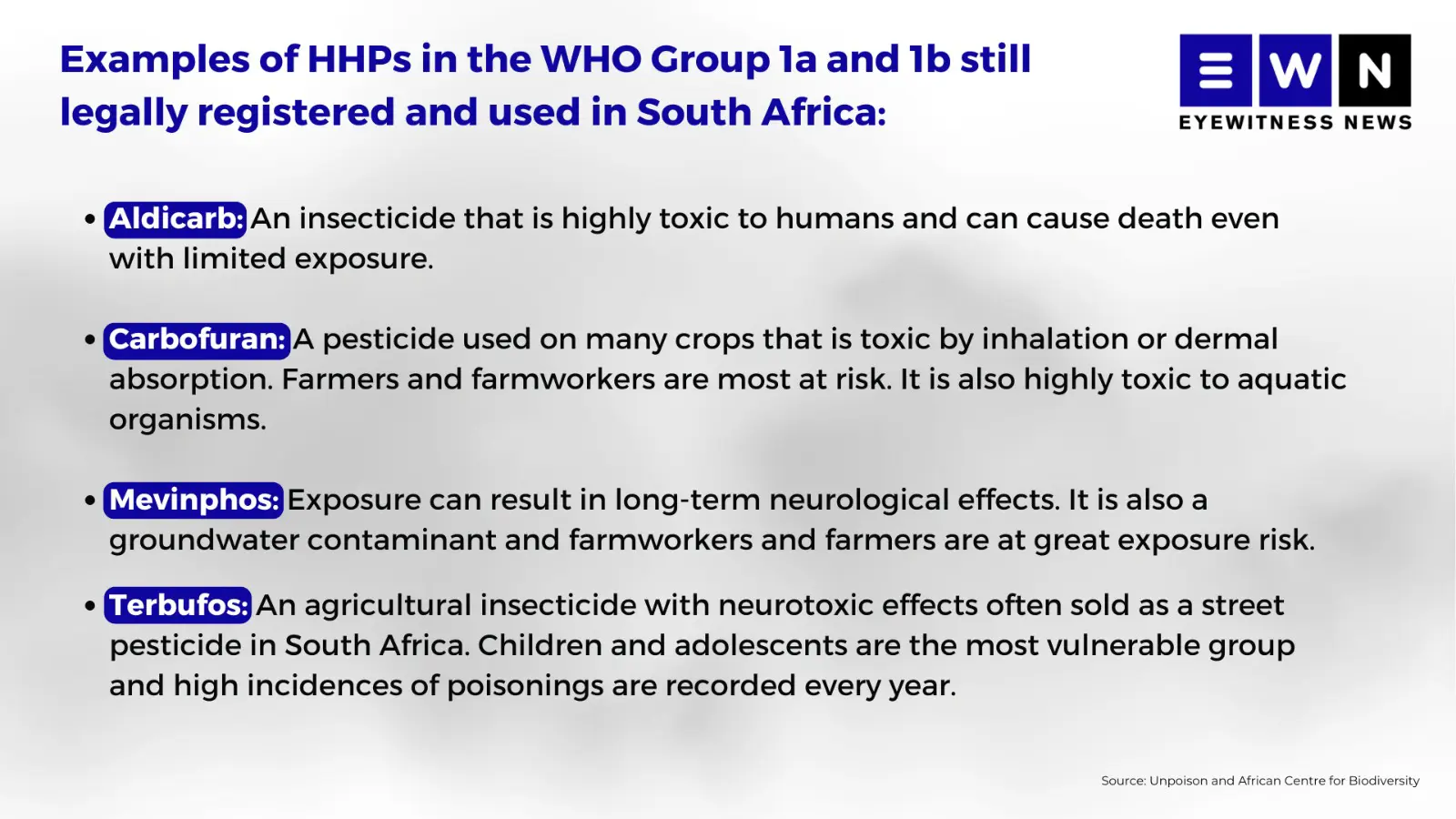

Graphic: Abigail Javier/Eyewitness News

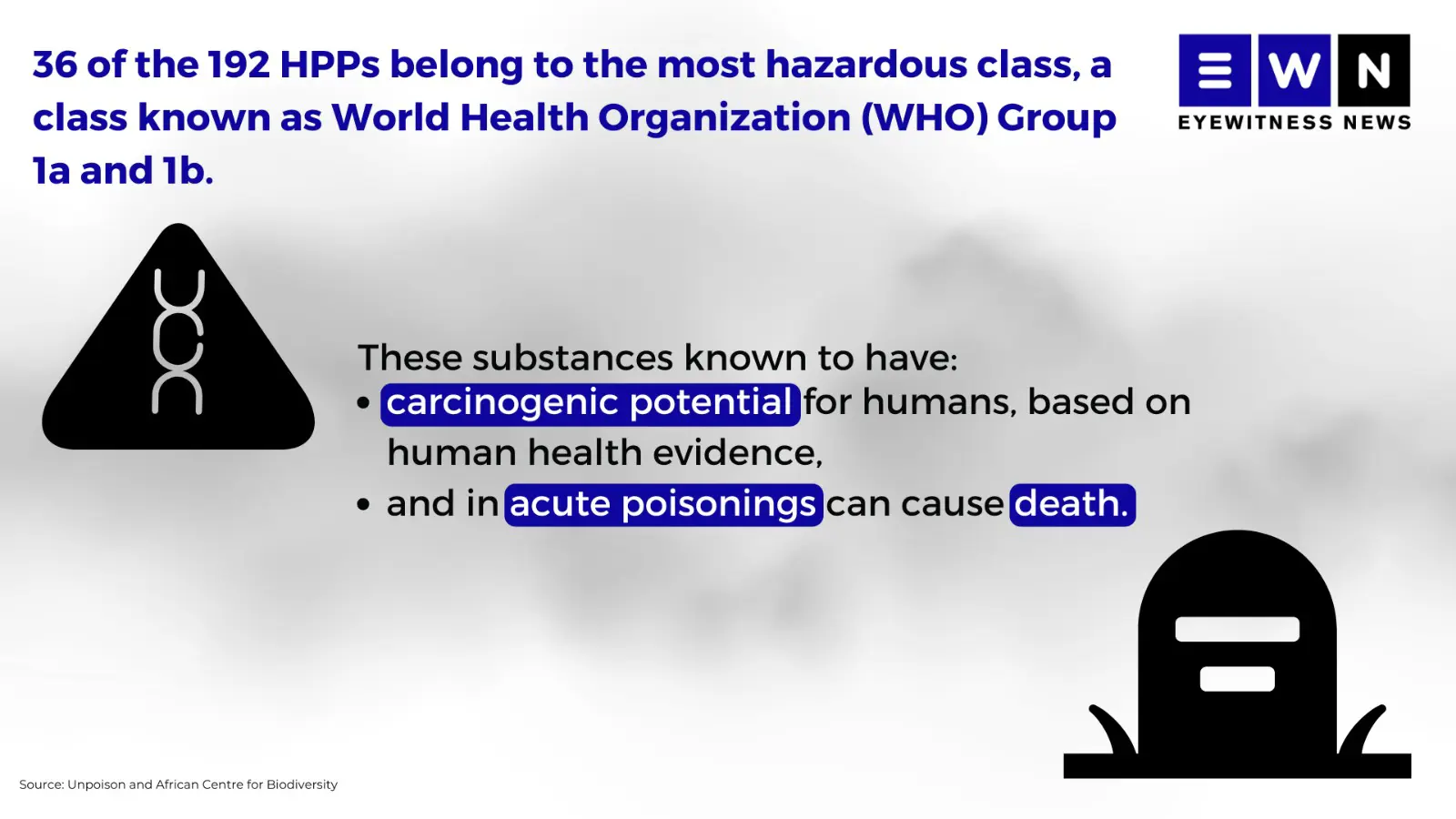

Graphic: Abigail Javier/Eyewitness News

Graphic: Abigail Javier/Eyewitness News

Whether granular, liquid or pellets, it is disturbingly easy for a person to accidentally poison themselves or others. Fatal if swallowed or if it comes into contact with skin, toxic to aquatic life, with long-lasting effects, and even suspected of causing cancer, terbufos is categorised as a level 1A HHP by the World Health Organization.

Days prior to our poisonous purchase, health minister Aaron Motsoaledi informed journalists that terbufos was the chemical found to have killed five children in Naledi, Soweto.

The children, Zinhle Masilela (7), Isago Mabote (8), Monica Sebetwane (6), Njabulo Msimango (7) and Karabo Rampou (8) died after experiencing severe stomach cramps, vomiting, and drowsiness.

Their friend Katleho Olifant (7) survived for a week in an intensive care unit at Lesedi Private Hospital before succumbing.

They allegedly consumed chips from a spaza shop on Thlathlane Street in Naledi last month.

Just moments before Motsoaledi went live on national television to make the announcement, the families of the children gathered at their local police station, where a State doctor explained how their children died.

In a leaked voice recording which EWN has in its possession, the doctor detailed how small black granules varying in amounts were found in the stomach and intestines of the five children.

“So, the five children that died on the same day, when we got their postmortems, we had to take their stomach and intestine contents, as well as their blood, for testing. In all five of the kids, the stomach and intestinal contents came back saying ‘terbufos’ was there [sic].”

“And then it was inside the food, all of them had consumed the food, different amounts, which had those black granules - I’m sure you have seen them, ‘halepherimi’.”

She explained how poisonous terbufos is to the nervous system.

“In your nervous system, there is a chemical that helps pass the message from one nerve to another so once the message has been passed, there’s an enzyme that breaks down that protein, so that it doesn’t send too many messages. So, what this poison does, it stops this enzyme that is supposed to break down the protein, so that the message doesn’t go far and then the system becomes overactive, and the chemical accumulates there.”

“That’s why when someone consumes the poison, they will have diarrhea because the message is being sent over in your system that the food must pass through your system quickly. This also results in twitching around the mouth or fasciculations [muscle twitches], because there is an overproduction or over presence of that chemical [sic].”

She says she conducted one of the postmortems of the two children who died in Naledi last year after allegedly consuming biscuits purchased from a spaza shop.

“The two children from last year, who ate biscuits, I did one of them as well and I have the results, it’s also terbufos.”

Griffon Poison Information Centre toxicologist Dr Gerhard Verdoorn says terbufos is extremely toxic, and can take as just one minute to kill you after ingestion.

“First thing that happens is there might be salivation, which is not always the case, but there’s definitely development of severe nausea, severe vomiting, shivering, a bit of muscle tremors - but not always - the pupils constrict slightly. And then people start becoming incoherent, they go into a coma, and then you die. What happens with terbufos, because it’s such a powerful neurotoxin, it affects the central nervous system and it prevents the person from breathing normally because it paralyses the diaphragm and the muscles, so if the diaphragm can’t move, you can’t breathe, and so you die from oxygen starvation - that’s what happens to people.”

According to a report by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights, Marcos Orellana, in 2022, 34 poisoning cases including five deaths occurred in Gauteng from an organophosphate suspected to be terbufos - the same chemical found in the intestines of the Naledi children.

The tombstones of the six children who died from terbufos poisoning in Naledi, Soweto. Picture: Katlego Jiyane/Eyewitness News

Hazardous substances and waste report by the UN by EWN on Scribd

The families of the Naledi kids continue to beg for answers - claiming they haven’t been provided with physical copies of the postmortem results.

Thabiseng Mabote, Isago’s mother, says their children didn’t deserve such a death.

“Do you know how our children died? If we could have recorded them, then the whole world could have seen how our children died. It’s very bad, they died in a very bad way, and they were children, they didn’t want to die. Isago even said ‘ha ke batle ho shoa, ke batle ho shoa, mama’ (I don’t want to die, I don’t want to die, mom). How do our kids die like that?”

The regulation of pesticides falls solely in the hands of the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development, which during Orellana's visit laid out their plans to ban the sale and use of some highly hazardous pesticides from 1 June 2024.

To the public's knowledge, this has not yet manifested.

If a person wanted to access registered pesticides, this can only be accessed through CropLife South Africa, for a fee - a concerning issue of transparency Orellana emphasised during his visit.

Gaping holes in regulations, outdated acts and a lack of enforcement has led us to where we are today - the emergence of "street pesticides" readily available in spaza shops and informal settlements, used to quell rampant rat and pest infestations, owed to a lack of waste collection and sanitation services, he added.

Get the whole picture 💡

Take a look at the topic timeline for all related articles.