MONDE NDLOVU: A heritage of black thought

Black thought is a key element in heritage that must be elevated to its rightful place, writes Monde Ndlovu.

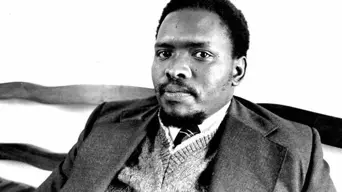

FILE: Late struggle icon Steve Biko. Picture: @BikoFoundation/Twitter

There is a well-known isiZulu saying that states, “indoda ayiqedwa”, meaning, man is a continuous mystery that deserves to be known as he becomes.

This saying often is uttered when the whole man/woman is not fully understood, and that there remains room for much understanding, in that, all humans have depth, irrespective of how you may feel about them.

South Africa is filled with public holidays and specific significant dates that must be commemorated and reflected on. Many of the dates celebrated have turned into moments of rest and dancing, and rarely moments of deep reflection. A good number of young people use these holidays to catch up on personal matters and not drive the kind of conversations the country needs have at this point in history.

We must ask what is the meaning of heritage in our time? And what is its significance to us today? What has been inherited? And what needs to change in this time that must be passed down to the next generation?

Heritage, in its simplest form is the societal norms, behaviours, languages, and wealth that is passed down to the next generation as a deposit into the future. In most cases, a crucial element in heritage is often missed, and that is the ideas and thinking frameworks that can be passed down from generation to generation. Black thought therefore is a key element in heritage that must be elevated to its rightful place.

Black people are a capable people, full of life and unique talents. In the month of September, we also celebrate the father of black consciousness, Steve Bantu Biko, who sharply placed black thought in its place. He emphasised that the mind of black people needs to be redeemed and through it, all black people can begin to live again by recreating themselves in their own way, on their terms.

The psychological damage caused by suppression is a matter of legacy, therefore a matter of heritage. Black thought militates against self-hate and degradation, upholding the highest principle of love. By loving ourselves, we extend a lifeline to the next generation in building from a place of love, and not a place of degeneration. The damage caused by the legacy of suppression remains, yet in the centre of this fact, black people have managed to rise above suppression and conceptualised progressive ideas.

The intellectual upheaval during suppression was premised on black thought, and how black people can think again for themselves under suppression. As a result, black people began to think more deeply about the economic landscape and how the economy must be owned, managed, and controlled by black people.

Underutilising black talent was no longer tolerated by blacks, leading to the creation of the National African Federated Chamber of Commerce (NAFCOC) in the 60s, the Black Management Forum (BMF) in the 70s, and other black organisations after them. These black organisations are a direct creation of black thought, and not an afterthought. They exist to lift the load of black people, and to create a home for economic development that will become a heritage and cradle for black economic empowerment, leading into the future.

Our heritage as black people cannot be poverty, unemployment, and inequality. Our heritage cannot also be the erosion of values, and the endemic and pervasive corruption that is eating our society. Neither can our heritage be the malfunctioning local government structure and its failures to serve our people. Our heritage cannot be the ongoing energy crisis and lack of decisive leadership on the way forward. Even in this context, “indoda ayiqedwa”, there is more to black thought than these challenges.

Our heritage needs to be contextual, and driven by justice, equity, and fairness. The creation of a new economic order that unleashes the potential of black people. What our white compatriots struggle to grasp is that by developing black people and transforming the economy will also be beneficial for them and their offspring. To date, transformation is seen as an expensive exercise and a mere tick box imperative.

Transformation ought to deliver a new order, it should take centre stage both in business and the public sector. Black thought has also brought about the transformational laws such as the Employment Equity Act and the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act. This is part of our black heritage, the ability to develop policy positions and turn them into laws that can transform our country.

Ubuntu is also a heritage of black thought, and needs to be woven into all management structures in the economy. Ubuntu as a philosophy, a way of life for all, and is deeply rooted into the soul of black people. The humanising effect of ubuntu needs to be harnessed and not debunked by western modes and perspectives of management, but we must Africanise management. This too is an idea of black thought.

The colour black is the key to creating other colours, and without it no other colour can be created. In the same way, without black people playing a central role in the economy, the future prospects of the country remain dim. What needs to be passed down to the next generation is that black thought and black thinking is key to driving the economic agenda, and that we are worthy to think and conceptualise.

We are free to think, free to act, free to become, and free to live.

This heritage must be preserved, and it should inspire successive generations, that the road to total liberation will need us to discharge transformation with courage and compassion.

“Indoda ayiqedwa”, there’s more to us, there’s more to our ideas, there’s more to our humanity.

Monde Ndlovu is a consultant for African leadership development.